She is the Bay Area’s Anthony Fauci, Santa Clara County’s most “essential” employee, the one who banished us from Sharks hockey games, canceled her own daughter’s high school prom — and eventually shut in 6 million Bay Area residents in six neighboring counties to slow the stampede of a deadly pandemic.

You could be forgiven if you’d never heard of Sara Cody before Jan. 31 — what seems like a century ago, when Kobe Bryant’s death was still what shocked us. That’s the day Dr. Cody was already feeling late, sitting at her dining room table in Old Palo Alto, gulping down a cup of coffee when her cellphone rang. It was 6:49 a.m.

“You’ve got your first positive,” the voice said.

A virus’ lethal journey

Right then, Cody — Santa Clara County’s Public Health Officer since 2013 — was positive that even by Silicon Valley standards, life as we know it here was about to change. Santa Clara County had recorded the Bay Area’s first case of coronavirus — the seventh in the U.S. Later that same day, President Donald Trump would ban most travel from China, where the stealth virus had begun its lethal journey across the planet.

But early that morning, Cody was preparing to tell the public it had already landed right here. Ever since, she has been in a furious race against the virus, making critical decisions that would shut down festivals and family gatherings, ban people from school, work and church — all in a grave attempt to save untold lives.

It was Cody who would eventually lead her Bay Area cohorts to pull the trigger March 16 on the historic seven-county legal order — the first of its kind in the country — that required residents to “shelter-in-place,” days ahead of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s similar mandate for the entire state.

And it is Cody who is carrying the burden of those decisions and the uncertainty of whether they will actually work.

“We just want to do everything we can to slow the train down,” Cody, 56, told the Bay Area News Group in a series of interviews this week, “so that when it hits the curve in the track it will not derail.”

‘When do you need me?’

In these unparalleled eight weeks, colleagues from Cody’s inner circle say, she has seldom hesitated. The morning she learned of the county’s first coronavirus case she was already calling two of her most-trusted advisers, now retired, from the health department. She had worked with them during the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and subsequent anthrax scare: her predecessor Marty Fenstersheib and Karen Smith, who had recently retired as the state’s public health officer and was on a girls’ ski weekend at Donner Summit when she got Cody’s call.

“When do you need me?” Smith asked.

“Right now,” Cody said.

When Smith arrived at the Public Health Department on Lenzen Avenue in San Jose that late January afternoon, she greeted Cody with a hug in the same conference room where she and Fenstersheib had interviewed the Stanford and Yale graduate 22 years earlier.

“We don’t hug anymore,” Smith said. The virus is too contagious.

Back in the early 2000s, with the country on edge after 9/11, Cody, Smith and Fenstersheib led the health department’s effort to build Santa Clara County’s model for a massive, coordinated emergency response to a bioterrorism attack or pandemic that included social distancing, shutting schools and the most extreme, mandating that people stay home. It’s the one they would turn to this month to slow the untraceable path of this new disease known as COVID-19.

“None of us really believed we would do it,” Smith, 63, said in a recent interview. “I was slightly terrified to think we were putting in place stay-at-home orders, tools that we think work but don’t really know.”

Real numbers a mystery

It’s too early to know whether the extreme measures will make a major difference. The number of infected people and deaths in Santa Clara County and the rest of the Bay Area continue to accelerate at eye-popping rates, as they are across the country, and fears are real that hospitals won’t be able to keep up with a tsunami of patients. Already, the Santa Clara Convention Center is being outfitted as a makeshift hospital ward, just in case. By Saturday afternoon, the Bay Area had surpassed 1,800 cases and recorded 46 deaths. But with testing still woefully limited, the real numbers remain a mystery.

“I wish we knew,” Cody said. “We can’t quantify it because we don’t have the surveillance tools to go out and widely test.”

Dr. John Swartzberg, a clinical professor emeritus of infectious diseases at UC Berkeley, gave Cody and her team high marks for their efforts.

“Santa Clara was out in front of this pandemic and deserves a great deal of credit for that,” he said. “In retrospect, they could have been more aggressive sooner. But if they are going to be criticized for that, all the other health departments would deserve greater criticism.”

Like Dr. Fauci, the infectious disease scientist and trusted voice on Trump’s coronavirus task force, Cody — who spent her first 15 years at the county investigating measles, meningitis and other communicable diseases — has risen from public obscurity to relative prominence in these last two months. And she has been both praised for her decisive leadership and criticized for doing too little or too much. In webcasts of her news conferences, Facebook commenters have griped about how long it took her to “CLOSE SCHOOLS NOW” and “the time to act was last week!”

After one news conference, she even became the subject of a viral meme when she implored citizens to refrain from touching their faces, then licked her finger to turn a page.

But Cody’s measured public pleas have been muted compared to the dramatic daily briefings of politicians like New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and often combative updates from the Trump White House. And she hasn’t scolded us, like bearded San Mateo County Public Health Officer Scott Morrow, who blasted scofflaws who are ignoring the stay-at-home order, declaring in a statement “you spit in our face” and “you will contribute to the death toll that will follow.”

Cody, with her neat bob haircut, tailored blazers and blue-framed glasses, is more reserved and practical.

“I’m a pretty calm person,” she said. “And never, never has my temperament been so useful.”

Not that she doesn’t get sentimental — “I’m a little bit of a crier at weddings and funerals,” she said — and she did briefly choke up on March 13 when she announced the legal order banning gatherings of 100 people or more.

“I was thinking about the people who live in our county,” Cody said, “the people that run small business, the people who are living right on the edge and how what I was doing was going to profoundly impact them personally and professionally.”

She said she knows how lucky she is — she lives in a house where each of her children have their own rooms in case they get sick and the family has a washer and dryer to keep them from taking trips to public laundromats.

Like everyone else, however, her family is enduring the same pressures of the stay-at-home restrictions. Her husband, a Stanford professor, “is complying with my order,” she said, working from home and keeping an eye on their teenage son, who is tasked with folding laundry and walking the dog, Alfie. They postponed a planned mother-daughter tour of colleges during spring break. And their daughter delivers groceries to Cody’s mother, who lives in the same house where Cody grew up five blocks away.

Since that first confirmed case in late January, the personal toll is mounting.

“It’s almost impossible to take a break,” Cody said. “First thing when you wake up in the morning, your email is full, your texts start flying, your phone starts ringing, then it happens all day until you go to sleep at night. Sometimes I’m not sure what day it is.”

The sentinel case

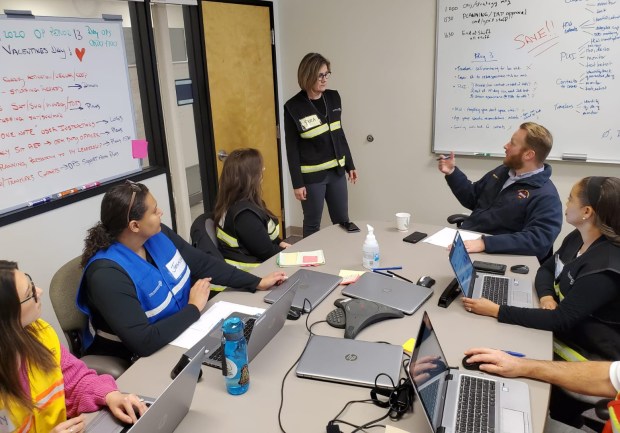

Cody has spent most of the last two months in the county’s Emergency Operations Center lined with wall-mounted computer monitors tracking cases, desks for dozens of county employees pulled from other departments and bottles of hand sanitizer and wipes scattered everywhere. Here, Cody has been grappling with questions, doubts and a frustrating lack of testing and information.

Through the years, she has learned that public health officers never have all the information they need and are always operating with uncertainty.

But the stakes are so much higher now.

The second confirmed case of coronavirus in the county came 48 hours after the first; both were travelers from China. But the criteria for sending swabs for testing to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta was so stringent and the bottleneck for test results so long, that the county was left hamstrung trying to figure out how big of a problem it really had. Not until nearly a month later, on Feb. 28, two days after the county was finally given authorization to use its own lab and judgment for testing, was the third “positive” confirmed.

It would be a “sentinel case” — a turning point for the virus’ spread across the Bay Area — a woman in her 60s with other health conditions. Unlike the first two, this was a clear case of “community transmission,” meaning the woman had become infected somewhere in our community, with no clear connection to a traveler.

“In very short order,” Cody said, “it became apparent we needed to start scaling up fast.”

Cody called old colleagues at the CDC, where she had done a fellowship two decades earlier, and within 24 hours a team landed at the San Jose airport to embed with her at the command center.

By then, Smith, the retired state health officer who cut short her ski trip, had created massive workflow charts that organized planning, logistics and operations.

The enormity of what lay ahead was daunting. With each case, Cody’s team began the meticulous process of interviewing every infected person, tracing back every place they had been and everyone they had contact with, and monitoring them in quarantine. The imperative was to stop the chain of transmission.

But as the number of cases escalated, keeping up became nearly impossible. On March 3, Cody started issuing guidelines every few days, recommending everything from telecommuting to cancellations of large gatherings.

By March 9, the sick woman in her 60s — the sentinel case — had died, and 43 cases had been confirmed, the highest of any county in California. Santa Clara County would now be branded across the country as a coronavirus “hot zone.” On that day, Cody announced her first in a series of legal orders that would force the Sharks to either cancel games or play to an empty arena, shut down the Cinequest film festival, close bars and clubs and cancel Boy Scouts fishing expeditions, library storytimes and Pilates classes.

In the midst of the frenetic operations center, Evelyn Ho, who moved from her job as the county’s community health planner to lead communications during the crisis, pulled Cody aside and asked how she was holding up.

“She talked about having very clear reminders for herself of how to stay centered in the moment, that the enormity of the decisions can’t be overwhelming,” Ho said. “She tried to center on breathing. She mentioned childbirth, taking that breath and breathing through the moment.”

The big decision

One of Cody’s greatest advantages through this crisis has been her longstanding and rare collaboration with the county’s legal staff. Over the years, Cody, County Counsel James Williams and chief assistant counsel Greta Hansen worked together on landmark lawsuits taking on the lead paint and opioid industries and, just a few months before the coronavirus crisis, imposing severe restrictions on tobacco vaping.

“You have to really know your partners and you have to trust them and they have to trust you,” Cody said. “And it can’t move fast unless you have that high level of trust. And we have that in our county. And I never realized how exceptional it was. But it turns out it’s pretty exceptional. And that’s allowed us to be nimble and be honest and lead.”

She would call on them Sunday morning, March 15 — the day of her biggest decision yet.

By then, 245 people across the Bay Area had tested positive and three had died from the virus. Passengers from the Grand Princess cruise ship showing symptoms were holed up on the third floor of a San Carlos hotel and at the Asilomar conference center in Pacific Grove. And in Gilroy, 66-year-old Gary Young was on a ventilator, in quarantine at St. Louise Hospital, one of the growing number of victims. He would die the next day, isolated from his family, as his daughter cried in the hallway outside.

“We need to do something more,” Cody told the lawyers, “and we need to do it right away.”

‘Embrace the risk and do it’

She had just gotten off the phone with health officers Tomas Aragon from San Francisco and Morrow from San Mateo County. They debated the race-against-time decision, the consequences for faltering — the kinds of stuff of Hollywood scripts.

They compared the trend lines of COVID-19 cases in the Bay Area with Italy’s a week and a half earlier, just before the situation there turned dire. If they didn’t take bold action, the Bay Area could be next.

“It was clear to me already how quickly it was moving, and that’s what gave me a sense of urgency,” Cody said. “We just needed to embrace the risk and do it.”

The three of them agreed: Ordering nearly 7 million Bay Area residents to stay at home was the best way to slow down the disease. It wouldn’t stop the spread, but it could buy time for hospitals to gear up for the onslaught, and create hope that the number of patients each day would be manageable.

By noon, seven health officers from six counties and the city of Berkeley — plus the two county lawyers — were on the phone, wrapping their heads around the monumental and sobering step they were about to take. What businesses are considered essential? Must it be ordered so soon?

They discussed how poor students out of school could still receive free lunches, that critical healthcare workers might have to stay home to care for their children, that employees on the financial fringes could lose paychecks. She stewed over the social and spiritual impact on canceled graduations and funerals and religious services.

“People need to nourish their soul,” she remembers thinking.

‘This is unprecedented’

But the expectation of massive loss of life, especially of the elderly and frail, was too great.

By afternoon, they were unanimous. Williams and Hansen stayed up all night putting the 10-page legal order together, making exceptions for hospitals, grocery stores, gas stations and other “essential” businesses. At lunchtime the next day, all seven gathered in a county briefing room, taking their places in two rows on the dais, spreading out six feet apart.

Cody was introduced first. Throughout the Bay Area, she said, 273 cases had been confirmed and the number was accelerating.

“I recognize that this is unprecedented,” she said. “But we must come together to do this and we know we need a regional response. … We must all do our part to slow the spread of COVID-19.”

It was the kind of clear leadership her inner circle had come to expect.

“She approaches those decisions in just the way you would hope, which is a profound commitment to doing the right thing and the best thing, no matter how challenging,” Hansen said. “And, you know, we would do anything for Sara.”

For Cody, despite all the frustrations and challenges she has faced over the past two months, “my overriding emotion much of the time has been gratitude,” she said. For her trusted advisers. For the relationships she built over the years.

Later this week, when the stay-at-home order has been in place for more than two weeks, she will have a better idea if her extreme measures are working. One thing is certain though, she said. “This is going to go on for quite some time.”

Until then, she said, there’s no time for second-guessing.

“We do not have time for that,” she said. “We are where we are. What can we do now? That’s the focus.”